The Médoc peninsula is a strategic location. This is borne out by the evidence of the various peoples who have occupied it throughout history. The Médoc peninsula borders the Gascony region. It has also been its gateway since the beginning of mankind.

Ancient elephant bones have been found at Le Gurp, the beach next to Euronat, and at L’Amélie, south of Soulac. Numerous flints found all along the Médoc coastline bear witness to the presence of man on our peninsula since the Neolithic period.

Many of the copper objects found in our region, as well as the flints, are on display at the Soulac Archaeological Museum. During the Bronze Age, the Médoc was a prosperous and populous region. Its inhabitants lived from agriculture, fishing and salt production.

At the same time, the Médules arrived, a Basque people who gave their name to our region: Méduli (Médoc). Our ancestors spoke Basque until the Romans arrived! But first came the Bituriges (Gauls), who left the estuary to the Médules. The Soulac Museum has a wealth of artefacts from this period, including the Soulac wild boar. This period was already rich in trade, as evidenced by the many types of coins found. The Gauls also provided the Médoc with an important road network, long before the Romans. The Romans brought vine growing with them (around 60 A.D.), which has never ceased since and is now famous. Even if it was the Gauls who invented the barrel!

From Euronat you can visit the Gallo-Roman remains at Jau and St Germain d’Esteuil.

Later, the first major road was built between Burdigala (Bordeaux) and the north of the Médoc: “la lébade”, a road that can still be seen at Avensan and on which we travel daily between Vensac and Grayan, where it is called “chemin de la Reyne”. The chemin de la Reyne, because later, Eleanor of Aquitaine returned to her country on the same road.

The Médoc suffered terribly from barbarian invasions throughout the first millennium. The Saxons and Visigoths razed many villages to the ground. Then came the Vikings, who destroyed everything in their path from the mouth of the estuary to Toulouse. The Vikings practically emptied the Médoc of its inhabitants. However, forts and batteries were built all along the Gironde to protect the city of Bordeaux.

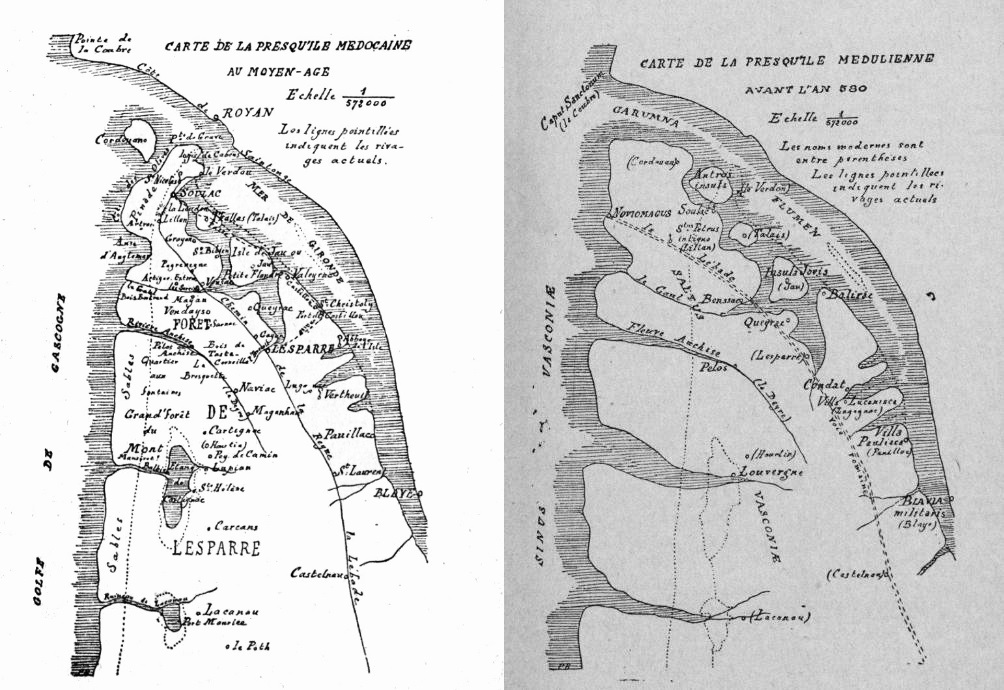

The geology of the Médoc peninsula (sand, marshes) makes it a territory with shifting boundaries, so much so that in the early Middle Ages Soulac was on the estuary. The rocky plateau of Cordouan was attached to the mainland, but at that time there was no mention of the famous lighthouse. However, by the 11th century, a monastery had been established there to guide sailors at night by lighting fires. Lesparre was then a river port.

Pilgrims to Santiago de Compostela from northern Europe and western France took the “coastal route” or “English route” to Portugal. They arrived in Soulac by boat and continued their pilgrimage on foot along the coastal road. The basilica of Notre Dame de la fin des terres, the hospital of Grayan (no longer existing) and its chapel are part of this heritage. The Tour de l’Honneur in Lesparre, the last vestige of the castle of the seigniory of the same name, is also a medieval monument.

The dunes eventually block the flow of rivers from the Landes to form Lac d’Hourtin, the largest freshwater lake in France, just 30km from Euronat. There are sailing clubs and many other water sports activities. You can also walk or cycle around the lake and through the surrounding forests.

The Médoc marshes were converted to salt production under the guidance of the Benedictine monks of Bordeaux. Salt-making continued until the end of the 19th century. They can still be seen in Talais, Soulac and Le Verdon. Today, they are essential for the maturation of the famous Médoc oyster, with its nutty flavour, and for king prawn farming in Le Verdon. The old oyster port is a popular attraction, and the old oyster huts are home to artists, dance halls and, in the summer, a night market.

In the 12th century, Eleanor’s Aquitaine came under English rule until the end of the 15th century. Bordeaux is still the most Anglophile of the French cities. The wine trade exploded thanks to the “British Isles” and we still have the capacity of 225 litre barrels from this period. 225 litres made 50 gallons, hence the 75 cl bottle, to get the round count of 300 bottles of wine from the contents of a barrel. Cases of wine are 6 or 12 bottles, which is 1 or 2 gallons!

Bordeaux is also the birthplace of Richard II. The castle of the Black Prince, or Edouard de Woodstock, his father, still dominates the Garonne at the entrance to the Pont d’Aquitaine. The Médoc peninsula is no exception, and the Prince left his mark on our region by building the first tower on the Cordouan cliffs, known as the “Black Tower”: a kind of dungeon that preceded the lighthouse, which was designed to guide ships. The tower has since been replaced by the lighthouse we know today, but one of the Verdon beaches has inherited its name: Plage de la Tour Noire.

The construction of the Cordouan lighthouse was decided under Henry II, then Henry IV, and completed under Louis XIII. It was raised by 20 metres to take its present form in 1789. It is a masterpiece of architecture and has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2021.

Over time, the Médoc peninsula became increasingly strategic. The port of Bordeaux became one of the most important in the kingdom, contributing to the reputation of the Médoc and Bordeaux wines.

In the 17th century, two forts were built on the Pointe de Grave: Fort Girofle, on the sea side, of which no trace remains today, its disappearance due to coastal erosion; Fort de la Chambrette, on the river side, which was also destroyed for the same reasons.

It was rebuilt under Louis XIV to protect Bordeaux. Together with Fort Médoc in Cussac, Fort Pâté (on the island of the same name) and the Citadelle de Blaye, further downstream on the Gironde, it forms part of the “Vauban Lock”.

There are more than thirty ports on the south bank of the estuary, including St Christoly. In the past, the river was used for all trade with Bordeaux (wine, timber, cattle, etc.) and fishermen still have their boats here. The village of Saint-Christoly is remarkable for its very homogeneous 18th century architecture and is well worth a visit.

On your way back, don’t hesitate to take your mind off things by stopping at the Cabaret Saint-Sabastien in Couquèques.

Agriculture is still very much alive in the Pointe du Médoc and there are several mills, including the one at Vensac, which is still in use. You can visit this mill and buy flour made on the spot!

In the 17th century, the difficulties associated with the silting up of the Pointe du Médoc and the disappearance of the Gabelle tax meant that salt lost its role as the main currency: the salt industry was gradually abandoned in favour of oyster farming. However, the marshes of our peninsula underwent a major transformation: they were reclaimed using Dutch methods and became known locally as “Les Mattes”.

Take the cycle paths towards Talais and along the estuary to discover this astonishing geography. A long protective dyke on which stand the carrelets, the famous fishermen’s huts so typical of our region. The marshes, criss-crossed by canals and locks, have become a remarkable ornithological reserve. In Le Verdon, the Logit and Conseiller marshes offer guided tours to discover the flora and fauna of the marshes. You’ll discover how important their role is in monitoring the region’s ecology.

Canoe trips will help you discover the flora and fauna of the canals. Hire one at the Port de St Vivien and paddle up the Guâ canal to the pond of the same name. During your cruise, you’ll be able to spot swans, coypu, turtles and all the other animals that inhabit our unspoilt region! On the way back, enjoy lunch or dinner at one of the many “guinguettes” in the harbour.

During the same century, the coastline also changed considerably. So much so that the sand invaded the village of Soulac and even covered its basilica. Forced to leave, the inhabitants founded Jeune Soulac a few kilometres away. In the following century, the basilica underwent major restoration work to bring it back to life.

It was at the beginning of the 19th century that the drying out of the moorlands of the Médoc peninsula was completed, with the planting of maritime pines all along the Gironde and Landes coasts. This immense pine forest is now the largest in Western Europe, covering almost a million hectares. It’s in the heart of this Landes forest that your favourite naturist centre nestles.

The timber trade is still very important in the Médoc. Gemmage, or the harvesting of pine resin, has been practised for decades in the Pointe du Médoc. Gemmage is the harvesting of pine resin to make turpentine. You can visit an exhibition dedicated to this activity in Vendays.

For those who enjoy walking, cycling or mountain biking, there is an incredible network of walks in the Médoc peninsula, from short family strolls to those for experienced sportsmen and women, you’re bound to find a circuit to suit you.

In the 19th century, 2 additional lighthouses were built at the Pointe de Grave and the Verdon to make navigation safer, which was becoming increasingly important at the entrance to the estuary. The Grave lighthouse, built in 1860, is still in use and now houses the Lighthouses and Signals Museum. The lighthouse of St Nicolas in 1871. It stands on the dune of the naturist beach of Plage St Nicolas in Le Verdon sur Mer. On the estuary, at Jau, the Richard lighthouse was built in 1843. Today it is a popular tourist attraction. A stone’s throw away, at the port of Richard, you can take to the skies in a hot air balloon! And if you want to see our region from even higher up, head for the Soulac flying club!

Coastal defence was a major project at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. During this period, the Médoc was constantly struggling against the erosion of the dunes. Between 1818 and 1946, the Pointe de Grave moved 720 metres eastwards! Between 1920 and 1939, George Mandel, the mayor of Soulac at the time, began to build dikes to prevent the commune of Le Verdon from becoming an island again.

The dykes began at the Pointe de Grave, with the pier, and extended to the north of Soulac. These dikes can still be seen today: the dunes of the Arros, Huttes and Cantines beaches overlook ponds with a view of the Cordouan lighthouse. At high tide, the sea overflows the dikes and fills the pools with salt water. You can catch a glimpse of them by taking the little tourist train at Pointe de Grave.

Tourism in the Médoc began with the arrival of the railway in 1875. Soulac became a very popular seaside resort.

At the same time, a number of beautiful houses were built with very local and distinctive architecture, a total of 500 villas between 1880 and 1940. A market hall was also built, which still houses the village’s daily market. The villas of Soulac are built with local materials: bricks from Soulac and Le Verdon, limestone from Charentes and wood. They are decorated with wooden lambrequins, stone cornices, ceramic motifs and other architectural decorations. They all have a name. Soulac has a remarkable architectural heritage, protected by an “Aire de Mise en Valeur de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine” (AVAP).

It’s all it takes to bring you back to the Belle Époque! You can do this every year at Soulac 1900. The event takes place on the first weekend in June. Everyone dresses as they did at the beginning of the 20th century! There’s a market, concerts and sometimes a steam train comes into Soulac station!

The first service to cross the Gironde began in the 19th century, but was limited to pedestrians disembarking from steamers at the Pointe de Grave pier. In 1927, a public service was introduced with the construction of a pontoon within the “Port Bloc”. This pontoon is still in use today.

In 1935, the first ferry, “Le Cordouan”, which could carry all types of vehicles, remained in service until 1960. Unlike its successors, it allowed passengers to travel on the forecastle! As the summer traffic increased over the years, 3 new ships were put into service. The “Côte d’Argent”, the “Gironde” and then the “Médocain” would “run” simultaneously during the summer for years to come. Today, two new amphidromes have taken over: more powerful, bigger and faster: “La Gironde and L’Estuaire.

The last major change to the landscape of the Pointe du Médoc occurred during the German occupation between 1940 and 1945. With the construction of the “Atlantic Wall”, dozens of bunkers, known locally as ” Blockhaus “, can still be seen all along the Côte d’Argent.

Despite their questionable origins, they are now an integral part of the beaches and dunes. Mr Lescorce in Soulac is a passionate man who will tell you all about the amazing history of the Royan Pocket during his visits. From the Pointe de Grave to Vensac, the Médoc was only liberated on 20 April 1945, a few days before the signing of the armistice.

At the Pointe de Grave, just after the ferry terminal and before the pier, you can see memorials dedicated to heroes of the Second World War, such as George Mandel, or a memorial dedicated to the Frankton operation.

Wine tourism plays an important role in the Médoc. The classification of Médoc and Bordeaux wines was established by Napoleon III. Follow the Route des Châteaux from Lesparre to Bordeaux and you’ll see almost all of them!

Magnificent 17th- and 18th-century châteaux await you, as well as plenty of wonderful and unusual wine tasting opportunities! For the Grands Crus, do not forget to make an appointment to visit the Chais.

Our peninsula is also home to many small wineries. Admittedly, they don’t have the reputation of the big names, but to each his own! You might just find the Médoc wine you love without spending a fortune!